Monthly Newsletter, Vol. 29, No.2 -February 2025

Strengthening solidarity and inclusion for social development

30 years ago, world leaders united around a groundbreaking commitment to put people at the centre of development. At the World Summit for Social Development in Copenhagen, they pledged to eradicate poverty, promote social integration, and achieve full and productive employment for all.

Efforts to make this promise a reality continue. Every year at the Commission for Social Development, the international community gathers to accelerate the commitments made in the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development, while addressing emerging global challenges.

This year’s session will convene from 10 to 14 February in New York under the theme: “Strengthening solidarity, social inclusion and social cohesion to accelerate the delivery of the commitments of the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development and Programme of Action of the World Summit for Social Development as well as the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”.

High-level panels and side events will bring together UN Member States, civil society, and experts to identify actionable strategies for building equitable and united societies.

As we approach the Second World Summit for Social Development taking place on 4-6 November in Doha, this year’s Commission highlights the importance of strengthening solidarity and social inclusion to achieve more cohesive societies, placing people at the centre of development. It is a call for renewed cooperation to ensure that no one is left behind in the global pursuit of social progress, justice and sustainable development.

As 2025 marks the 30th Anniversary of the 1995 Copenhagen Declaration, the Summit in Doha represents a pivotal moment for the global community to renew the commitment to inclusion, equality, and sustainability. It will be a chance to come together for a more resilient world, where everyone is included.

For more information: 63rd Session of the Commission for Social Development

Expert Voices

“Partnering as equals in co-creating a better future”

Expert Voices

“We will not be able to make progress on the Sustainable Development Goals without […] a full sense of partnership,” said ECOSOC President Ambassador Bob Rae, as we spoke with him ahead of the 2025 ECOSOC Partnership Forum on 5 February at UN Headquarters in New York. “The actual implementation of most of the agenda of the United Nations depends on the deep engagement and commitment of civil society.”

What does partnership mean to you?

“I think it means everything. One of the key lessons that I’ve learned over my political and diplomatic life is how to work in collaboration with Member States, with civil society representatives, and all kinds of groups and people who want to engage. It is really at the heart of ECOSOC’s mission.

The UN Charter makes it clear that we are the institution that has the primary responsibility for engagement with civil society. The record shows that our key role reflects the presence of many civil society organizations in the drafting process of the of the Charter itself, and in the hopes that people had for the UN organization as a body that would be operating on a different basis and with a different approach than the League of Nations.

For me, partnership means recognizing the legitimacy and the equality of civil society groups who are coming to engage with the organization about the work of the organization, and about the challenges facing the world. The reality of life is that we could not possibly deal with these challenges without the full engagement of civil society, labor organizations, business communities, and all kinds of non-governmental organizations.”

What advice would you give to emerging leaders looking to create impactful collaborations?

“The first advice is to be aware of the extent to which civic life in every country is driven, not just by political parties and by governments, but also by businesses, labor organizations, civil society organizations of every kind. They are an essential part of the activities of the United Nations.

Take for example the Sustainable Development Goals. We will not be able to make progress on the SDGs without them, without everybody, without a full sense of partnership. And it’s not just a matter of States listening and then saying thank you, we’ll go off and do what we’re going to do. No, the actual implementation of most of the agenda of the United Nations depends on the deep engagement and commitment of civil society.”

How do you address the power dynamics that can arise in partnerships, particularly between developed and developing countries?

“We need to appreciate that we’re the product of the end of these two horrific global conflicts – World War I and World War II. We are also the product of the critically important process of decolonization. It’s fair to say that although political decolonization has occurred, the necessary changes in economic systems, social structures, cultural perspectives, and attitudes are still far from fully realized.

I think we need a full appreciation of what it means to be an equal member of the global community. As sovereign states, we are all equal, but we’re also equal as human beings, and we’re equal, as all of us have as much right to be at the table as anybody else.

The principle of global solidarity, the principle of global equality, the principle that we’re all here together as every nation state and every part of the world has an equal right to be here.”

What legacy do you hope to leave through your work in advancing partnerships for sustainable development?

“The ECOSOC year with real public engagement starts in February and lasts until July. During that period, we have a key opportunity to engage with civil society on some very important issues around the Sustainable Development Goals and how we can create more dynamism behind those goals. I think it’s critically important for us to really focus on the goals as the overarching theme of everything that we try to do.

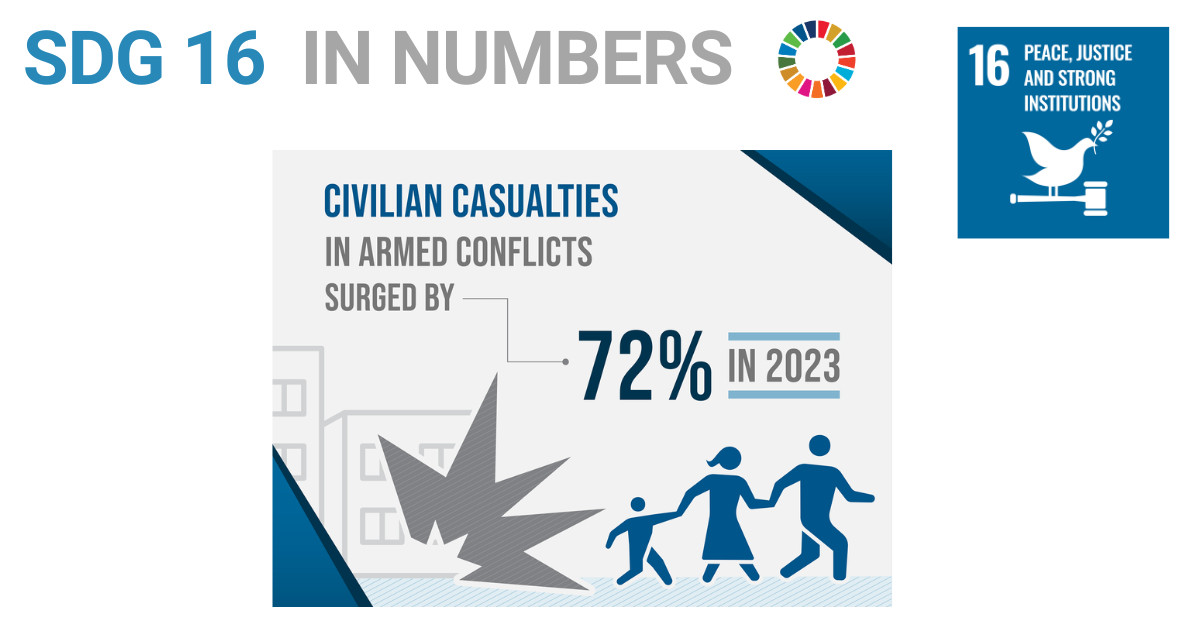

Within those goals to emphasize a few things that matter for me. The issue of displacement and the issue of the impact of war and conflict and climate change on people, is something that we need to better understand. We have more people who are displaced and who are living in refugee camps of one kind or another around the world, than we’ve had since 1945. We have a greater human challenge here and sometimes we say, well, that’s a Geneva issue, it’s a UNHCR issue. No, it’s a global issue.

The other one is the impact of artificial intelligence as it is now clearly affecting our economies, our life, and our work. We’re just beginning to understand better how impactful the development of these new technologies is going to be on our countries.

As we navigate these shifts, it is essential to approach this in a spirit that reinforces the fundamental equality between men and women, and between all those who are working in the world, and that we need to break down barriers and sources of discrimination between us.

This mindset must guide us as we move from the Partnership Forum to more detailed and expert panels on tax matters, accountability and a whole range of other topics. It also underpins our engagement in milestone public events like the Commission on the Status of Women, the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, the Youth Forum, the High-level Political Forum and […] some other events that are happening like the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development and the Second World Summit on Social Development in Doha.

These are all part of the ways of recommitting to the Pact for the Future and to the agreements that we made last year with respect to how we go forward.

One of the things that I learned during my work in government, is about the importance of making people feel that they are co-creating policy or co-creating legislation. How can we really commit as equals to co-create the progress we need to make? This is something that the Partnership Forum is all about. A meeting of partnership, based on a relationship between equals who are co-creating a better future.”

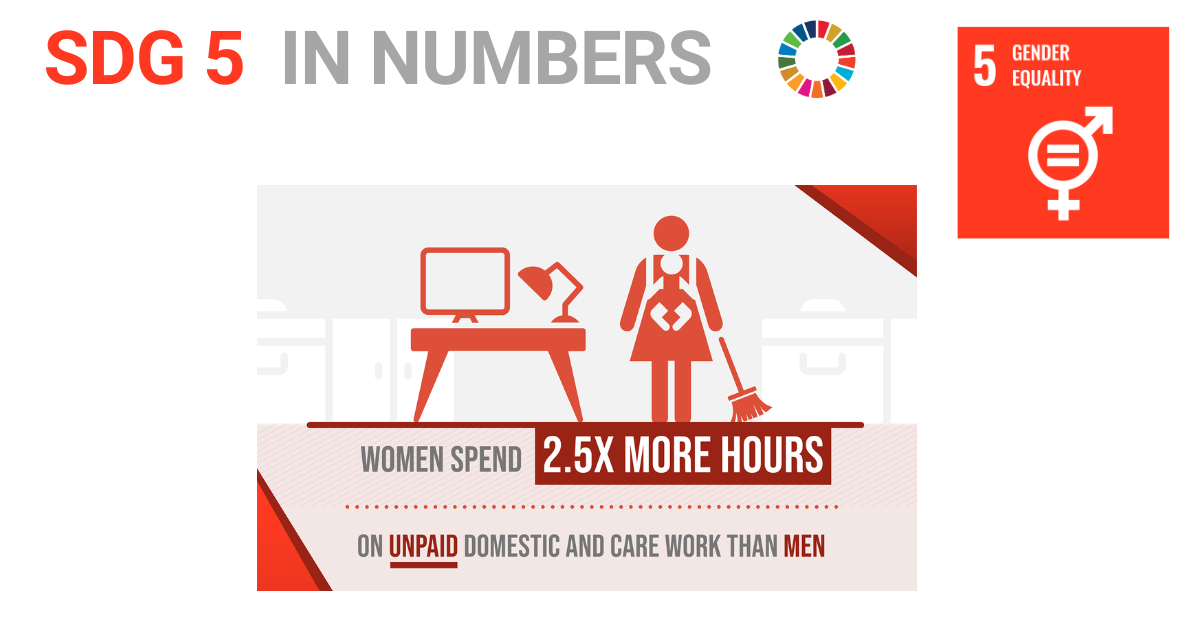

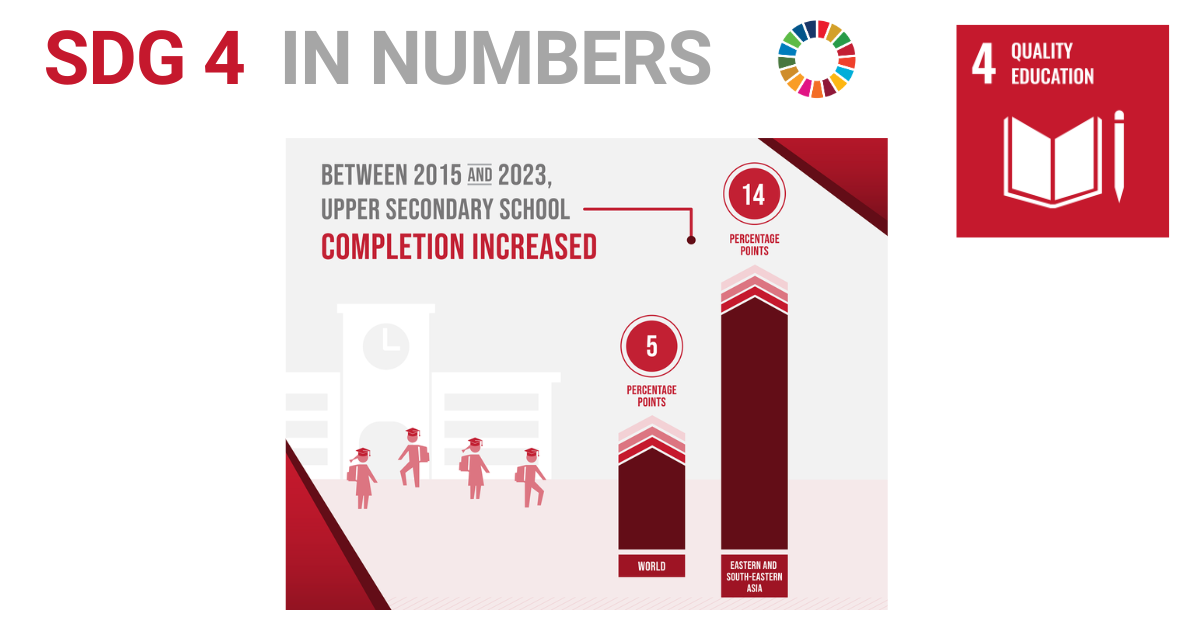

The 2025 ECOSOC Partnership Forum will focus on the 2025 ECOSOC and High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) theme: “Advancing sustainable, inclusive, science- and evidence-based solutions for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals for leaving no one behind,” placing a special emphasis on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will be reviewed at the 2025 HLPF, namely Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being); Goal 5 (Gender Equality); Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth); Goal 14 (Life Below Water); and Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

Follow the UN ECOSOC President on social media, via Instagram and X, and be sure to sign up for the ECOSOC Newsletter here.

Photo: UN Photo/Loey Felipe

Things You Need To Know

“Let’s make 2025 the year we put the world on track for a prosperous and sustainable future,” urged UN Secretary-General António Guterres, as UN DESA released its global economic outlook last month in the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2025. Here are 6 things you should know about the global economy:

1. Global economic growth remains below the pre-pandemic average.

The report projects global economic growth to remain at 2.8 per cent in 2025, below the pre-pandemic average of 3.2 per cent. While easing inflation and monetary easing offer some respite, challenges such as trade tensions, geopolitical conflicts, and elevated debt burdens threaten the outlook.

2. Regional growth prospects vary widely.

East and South Asia will remain global growth drivers in 2025, with projected expansions of 4.7 per cent and 5.7 per cent respectively. Africa’s growth is forecast to improve slightly to 3.7 per cent but is restrained by high debt costs and climate-related challenges.

3. The outlook is precarious for many countries.

Many vulnerable economies are seeing downward revisions to their growth outlook, which remains well below pre-pandemic trends. This weak performance is compounding risks to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, with progress in reducing poverty continuing to be slow and uneven.

4. Falling inflation creates room for monetary easing, though challenges persist.

Global inflation is projected to decline further, from 4 per cent in 2024 to 3.4 per cent in 2025, offering relief to households and businesses. However, many developing countries continue to grapple with elevated inflation, particularly in food prices.

5. Governments are adopting gradual fiscal consolidation to improve debt sustainability and rebuild fiscal space.

Fiscal pressures are particularly severe in Africa, where rising debt-servicing burdens are increasingly diverting resources away from essential public services and investment. On a GDP-weighted basis, African governments allocated 27 per cent of revenues to interest payments in 2024, up from 19 per cent in 2019 and 7 per cent in 2007.

6. Critical minerals play a vital role in advancing the energy transition and supporting sustainable development.

Resource-rich developing countries can benefit from rising global demand for critical minerals to create jobs and boost sustainable development. “Critical minerals have immense potential to accelerate sustainable development, but only if managed responsibly,” according to Li Junhua, UN Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs.

Learn more in the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2025 here.

Solar energy is the most abundant of all energy resources and can even be harnessed in cloudy weather.

Solar energy is the most abundant of all energy resources and can even be harnessed in cloudy weather.